The real founding origins of the Knights Templar, revealing the true purposes and character of the Order, proving it became an independent sovereign Principality in 1120 AD reconfirmed in 1139 AD, and proving its foundations which supported its later survival and modern restoration.

Many websites of medieval history interest groups, and various Templar themed revival groups, tend to rely upon only the standard short summary of how and why the Knights Templar were supposedly founded. Repeating the typical mainstream story apparently caters to popularized misconceptions from fraternities and the entertainment industry. That superficial and overused approach merely ‘glosses over’ a wealth of fascinating, revealing, and inspiring history, instead saying only what people seem to expect to hear.

Many websites of medieval history interest groups, and various Templar themed revival groups, tend to rely upon only the standard short summary of how and why the Knights Templar were supposedly founded. Repeating the typical mainstream story apparently caters to popularized misconceptions from fraternities and the entertainment industry. That superficial and overused approach merely ‘glosses over’ a wealth of fascinating, revealing, and inspiring history, instead saying only what people seem to expect to hear.

The standard narrative, usually focused on glorifying knightly battles, or on speculation about the corrupt French Persecution of the Templars, generally fails to express the genuine character and missions of the Templar Order.

To understand the authentic Templar way of life of Chivalry, it is necessary to first define what it actually was – and what it was not. As the Greek philosopher Socrates famously said (ca. 430 BC), “The beginning of wisdom is the definition of terms.” [1] The only way to understand what the Order really was and what it really did, is to first examine the forgotten facts of its foundations.

Here, in this work from the direct continuation of the original and restored Ancient Order of Knights of the Temple, the world can finally rediscover the true history of the real founding origins and purposes of the Templar Order.

The foundations presented here focus on the facts most relevant to supporting the later Survival and modern Restoration of the Templar Order.

The idea of Templars as “Crusaders” is proven to be very different than commonly described:

The First Crusade (1096-1099 AD) was fought almost 20 years before the Templar Order was established under the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1118 AD. In the Temple Rule of 1129 AD, the Templars actually rejected the idea of Crusades as supposedly to overcome Muslims or Islam, and criticized that it “did not do what it should, that is to defend… but strove to plunder, despoil and kill” (Rule 2). [2]

The Third Crusade (1189-1192 AD) was to retake only a few Christian territories captured by Salahadin, and establish the Kingdom of Cyprus to relocate Christians back towards Europe, ending with a peace treaty. The Second Crusade (1147-1149 AD) and Fourth Crusade (1202-1204 AD) were to defend Byzantine Christians against early Turkish imperialism, and later battles were to defend Europe against invasion by the Ottoman Empire (from 1299 AD).

The standard narrative of “protecting pilgrims” travelling to the Holy Land is proven to be a very limited sideline activity:

This merely symbolic military presence was mostly to earn the Royal Patronage of the Kingdom of Jerusalem [3] [4]. The Temple Rule (as amended ca. 1150 AD) evidences that a small force of only “ten knight brothers” were actually assigned to “guard the pilgrims who come” (Rule 121) [5]. This was essentially the early “day job” of the Templar Order, to support their real founding mission, which is much more interesting.

The speculation about the Order as a “heretical secret society” is proven categorically false:

The Temple Rule, as its founding charter, requires the Order to operate “according to canonical law” (Rule 9), as a “canonical institution… according to the precepts” of the Code of Canon Law (Rule 274) [6], which prohibits both heresies (Canon 278, §3) and secret societies (Canon 285, §§1-2) [7]. The Temple Rule also requires all ceremonies to be performed only openly “in Council”, thus prohibiting any secret or unofficial practices beyond what is publicly declared (Rule 678) [8].

The truth of the real origins and foundations of the Knights Templar, and thus its real purpose and missions of Chivalry, exceeds all expectations of the mainstream narratives:

The Order of Knights of the Temple was actually established to first recover the Ancient Priesthood from the Library of the Temple of Solomon, to thereby recover the “lost” sacred knowledge as the collective heritage of humanity, to then restore the Pillars of Civilization from the last Golden Age in ancient Egypt, to establish Magna Carta human rights and Common Law, and to finally lead Europe out of the Middle Ages and into the uplifting spirit of the Renaissance.

The foundations of the Templar Order were actually Royal Patronage by the Kingdom of Jerusalem from 1118 AD, elevated to full Royal Protection granting permanent independent sovereignty in 1120 AD, becoming a High Court for Crown Regency as Defenders of Kingdoms by ca. 1129 AD, achieving legal status as a permanent Non-Territorial Principality in its own right since 1129 AD, recognized by the Vatican as having its own Ecclesiastical Sovereignty of the Templar Priesthood in 1129 AD and 1139 AD, and receiving additional Sovereign Protection from the Vatican in 1139 AD.

These foundations were strengthened by cooperation and support from the Vatican, all while maintaining independence from the Vatican for the future.

All of these facts are fully presented here in this report, complete with evidence as primary source references in the historical record, to restore the fullest understanding of genuine Templarism in the modern era.

![]()

As a result, the Templars became Defenders of the Church not only for their strategic military skills, but much more for recovering and restoring the Ancient Priesthood from the Temple of Solomon, making them Guardians of the origins and foundations of Christianity itself.

The earliest inception of the Knights Templar, and the initial motivation for the first Templars to explore the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem, began with a mission of Biblical archaeology, sponsored by the Cistercian Order.

This mission was commissioned by the Saxon Cistercian, Saint Stephen Harding, Abbot of Citeaux, the mentor of the Cistercian Bernard de Clairvaux (who would soon become the Templar Patron Saint Bernard).

French historians explain that Saint Stephen of Citeaux pursued a “sudden interest” in translating Old Testament texts, because “they revealed that a hidden treasure lay buried beneath the Temple Mount. This is why the lay [nobility] Patron of the Cistercians, Count Hugh of Champagne, went to Jerusalem and instigated his vassal” Hughes de Payens “to establish” the Templar Order at the Temple Mount. [9]

British historians confirm that this “Treasure of the Templars” was what the Knights “did find during their excavations of the Temple of Jerusalem”, which most scholars believe were “documents relating to the true nature of Christianity and Biblical matters” [10].

Archaeology has established that this Temple under Temple Mount contained a library of sacred scrolls, which was the Library of the Biblical King Solomon [11]. Therefore, the founding Knights Templar were actually archaeologists, and arguably even “librarians”, as much as they were Warrior Monks.

The archaeological site excavated by the founding Knights Templar was in the underground layers of Temple Mount, also called “Mount Moriah”. This is the site of the “First Temple” built by King Solomon (ca. 960 BC), which covered the full territory of Temple Mount, thus running underneath and around all later structures.

This is the same site as the “Second Temple” (516 BC), reconstructed by King Herod as a replica of Solomon’s Temple (ca. 18 BC), thus often called “Herod’s Temple”, which was destroyed by the Romans (70 AD). The top of the Mount in Old Jerusalem features the landmarks Dome of the Rock (692 AD) and Al-Aqsa Mosque (705 AD), adjacent to each other.

The fact that the site of Temple Mount contained the Biblical ancient Temple of Solomon, was confirmed by the 1st century historian Flavius Josephus, who documented that Herod’s Temple was built on top of the same site of the original King Solomon’s Temple [12].

This was further confirmed by the 5th century Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea, as documented by the 19th century British Barrister and historian Charles Addison, establishing that “Solomon began to build the house of the Lord at Jerusalem on Mount Moriah [Temple Mount]” [13].

This was additionally confirmed by the 13th century Pope Urban IV, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, also as documented by the 19th century Barrister Addison, establishing that during the 12th century, “the Temple on Mount Moriah” was described “by the monks and priests of Jerusalem… as the Temple of Solomon, whence the [knights] came thenceforth to be known by the name of ‘the Knighthood of the Temple of Solomon’.” [14]

Both the historical record and Biblical scholarship evidence that the Temple of Solomon, excavated by the founding Knights Templar, was in fact a Pharaonic Egyptian Temple.

The Kingdom of Solomon (ca. 970-931 BC) covered a wide territory, which included Egypt. The Old Testament records that “Solomon reigned over all kingdoms from the river [Euphrates]… and unto the border of Egypt” (I Kings 4:21) [15]. In the earlier Greek for this passage, the word for “unto” is ‘heos’, meaning “down” as in “continuing through”, and the word for “border” is ‘horion’ meaning a wider and inclusive “region” [16] [17].

Accordingly, Solomon was a ruling King “down through” and thus including the “region” of Egypt. Archaeology of the 19th century confirms that Solomon ruled “a kingdom that stretched from Egypt to Iraq”, including both countries [18].

Therefore, the Temple of Solomon, built by King Solomon, surely would have been a Pharaonic Egyptian Temple, as the Egyptian Priesthood was the most highly developed and dominant for over 4,000 years before Solomon.

An early 19th century lawyer historian documented that the Temple of Solomon featured a library of the Ancient Royal Secret Archives from Egypt: “It was hinted in some of the inscriptions that the great Temple at Jerusalem was built by Solomon more to protect these Archives than anything else.” [19]

The fact that the Temple of Solomon was Pharonic Egyptian is confirmed by multiple events and details in the Old Testament:

“Solomon made affinity [alliance] with Pharaoh King of Egypt, and took Pharaoh’s daughter” for his first wife (I Kings 3:1-3), before starting to build the Temple “in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign” ca. 966 BC, completing construction ca. 959 BC (I Kings 6:1,38).

This strong and close alliance with the Egyptian Pharaoh evidences that the Temple of Solomon was in fact an Egyptian Temple. As Solomon’s first wife was the Pharaoh’s daughter, certainly the first Temple built to God was a Temple of the Pharaoh’s Ancient Priesthood of the same God.

Then “Solomon loved many strange [foreign] women… his wives turned away his heart after other gods”, and he built “an high place” of a Temple for each deity “for all his strange [foreign] wives” (I Kings 11:1-8). As Solomon built a Temple for the deities of all his foreign wives, surely he built the first Temple of God as an Egyptian Temple for his first Egyptian wife.

That the Temple of Solomon was an Egyptian Temple, is confirmed by a major event in the Old Testament, when ca. 930 BC “Shishak King of Egypt” (the Pharaoh Sheshonq I, who ruled 945-924 BC) “took away all… which Solomon had made” from the Temple of Solomon (I Kings 14:25-26), specifically because the new Priests under a new King “had transgressed against the Lord” (II Chronicles 12:2-4, 9).

This evidences that the Temple of Solomon itself (thus including all of its Solomonic artifacts) was in fact Pharaonic Egyptian, such that the later emergence of Babylonian sacrilege in that Temple required a military campaign, to return the Holy artifacts back to Egypt where they originated from.

This is further confirmed by another event in the Old Testament, when Babylonians invaded Jerusalem ca. 605 BC (Jeremiah 6:22-23), and “Then Pharaoh’s army was come forth out of Egypt” (under Pharaoh Nekau II, who ruled 610-595 BC) to defend the city to protect the Temple of Solomon (Jeremiah 37:5).

The Old Testament also reflects the historical knowledge that Herod’s Temple was a very close replica reconstruction of Solomon’s Temple, and further confirms its ancient origins from Pharaonic Egypt.

God showed the Prophet Ezekiel the Holy of Holies within the Temple of Solomon, blaming Herod for corrupting the positive Ancient Priesthood with negative Babylonian practices of idolatry and blasphemy: God specifically condemned what the new Priests “do in the dark, every man in the chambers of his imagery… they say, The Lord seeth us not, the Lord hath forsaken the earth.”

However, what Ezekiel actually saw of the Temple itself was not the subject of that condemnation, but merely a description of how it was a replica of Solomon’s Temple: “I went in and saw… beasts [animal figures], and all the idols [statues] of the house… portrayed upon the wall[s] round about” (Ezekiel 8:10-12).

University Bible scholarship established that when Ezekiel looked into the Temple, he saw “paintings… and other mythological scenes, motifs which seemed to point to syncretistic [combined] practices of Egyptian provenance [origins].” [20]

The 1st century historian Flavius Josephus (ca. 37-100 AD), who served as the Governor of Galilee, personally witnessed Herod’s Temple (before its destruction in 70 AD), and documented it as a replica very closely following the Biblical descriptions of the Temple of Solomon, specifically featuring representations of the heavenly sphere of the constellations related to the ancient Egyptian Priesthood.

Flavius Josephus, by his own site research of Herod’s replica Temple, established that the Temple of Solomon contained decorations of “mystical interpretation… all that was mystical in the heavens… signs, representing living creatures” [21], and “figures of living creatures within it” [22]. This is a clear reference to the Egyptian veneration of Angels and Saints, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and other Egyptian inscriptions, all featuring animal figures.

Templar heritage from the Ancient Egyptian Priesthood is not in any way “pagan“, but is in fact the underlying origins and foundations of all canonical Apostolic, Catholic and Orthodox ceremonial practices as taught by Jesus and the Apostles.

Both Saint Augustine and Saint Jerome, in letters to each other in 418 AD, fully recognized the Ancient Egyptian Priesthood as the original “true religion, which… began to be called Christian” [23], and which “established anew the Ancient Faith” within Christianity [24].

The Egyptian religion was always monotheistic, worshipping One God as the creator, called the “Aten”, depicted as an energy field orb radiating rays of energy with hands at the ends, from the hieroglyph “Ka” meaning “Spirit”, establishing the Christian concept of the “Holy Spirit” from God [25] [26].

The idea of so-called ‘deities’, ‘gods’ and ‘goddesses’ of Egypt was only a mistranslation of the hieroglyph “Neter”, which actually means “Holy”, “Angelic” or “Saintly”, and the plural “Neterwoo” meaning Angels and Saints as “Holies from God” [27]. Oxford University established that Holy people were “deified” by being ceremonially “assimilated” with an Angel, meaning canonized as Saints, in the same way as for Catholic Saints [28].

Thus, the statues and stone reliefs of the Egyptian Temples and the Temple of Solomon were no different than the Catholic and Orthodox practice of venerating statues and icons of Angels and Saints throughout the Churches and Cathedrals of Europe. The Vatican in 787 AD confirmed “the veneration of holy images” as statues and icons [29], and actually declared that “All writings against the venerable images are… heretical” [30].

Many historians concluded that the first Knights Templar essentially stayed underground deep within the Temple of Solomon, mostly not resurfacing except to send for supplies, for several years:

“The Templars’ apparent lack of activity in their formative years, seems to have been due to some form of covert project beneath the Temple of Solomon or nearby, an operation that could not be revealed to any but a few high-ranking Nobles.” [31] [32]

University historians confirmed that the founding Knights Templar conducted archaeological excavation of the Temple of Solomon for a full nine years [33].

These facts evidence that what the Templars found underground within the Temple of Solomon was so fascinating, inspiring, and voluminous in quantity of texts and artifacts, that it drove them to “obsession” (or at least devout dedication), relentlessly processing the discoveries on-site, despite difficult underground living conditions, for nine whole years.

During the 12th century, archaeology did not yet have the benefit of the late 18th century French expeditions and Rosetta Stone to decode hieroglyphs, nor the late 19th century British explorers and early 20th century Egyptian Sign List of Sir Alan Gardiner.

Therefore, the Knights Templar received support from the Egyptian Sufi Mystics, the Al-Banna branch of the Sufi Order based in Luxor. When these Sufis learned of the first Templars excavating the Temple of Solomon, they immediately traveled from Egypt to Jerusalem to assist the Christian Knights.

The Sufi Mystics knew that the Temple of Solomon was Pharaonic Egyptian, based upon esoteric sacred knowledge from the most ancient Magi Priesthood of Melchizedek. They knew that the Templars would need ancient Egyptian initiatory knowledge to understand their archaeological findings. They also knew the fundamental importance of the Magi Ancient Priesthood to Christianity, telling the Templars: “You may have the Cross, but we have the meaning of the Cross.”

Therefore, by this generous voluntary support, motivated by a shared dedication to the most ancient traditions of Holy Mysticism, the Egyptian Sufi Order extensively trained the founding Knights Templar throughout their formative nine years of excavating the Temple of Solomon. [34]

The founding Templar Knights, as a direct result of their initial archaeological findings excavating the historical Temple of Solomon, established the Order of Knights of the Temple in 1118 AD, named after that Temple as the source of their authority. They then lived mostly underground studying the Temple throughout nine years.

The resulting time frame revealed by these facts is highly significant: The Templars resurfaced from excavations on the 9th year after the Order being established under Royal Patronage of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Vatican gave additional Patronage to the Templar Order, ratifying the Temple Rule as a Papal Decree in 1129 AD, on the 11th year after the Order was established.

This means that the Vatican granted the Templars what many historians call “unprecedented power” or “unlimited power”, a short two years after they resurfaced from the Temple, only one year after they would have finished sufficient processing of their archaeological discoveries.

The context of these facts is deeply revealing of the importance of the archaeological discoveries made: Of that one-year interval, it would take approximately three months for the Knights to travel from Jerusalem to the Vatican in Rome, at least three months for the Vatican to make official decisions, and at least six months to prepare and implement connecting the Knights Templar with the Vatican, which is precisely what happened.

This means that the Templars basically “ran” to the Vatican, directly and immediately, to present their discoveries as fast as possible. It also means that the Vatican responded overwhelmingly to that presentation, moving as quickly as any such international institution possibly could, to “immediately” grant the Templars unprecedented powers as an Order of Chivalry.

These facts evidence that what the Templars discovered in the Temple was so important, and had such potential to so profoundly affect the foundations of Christianity and the authorities of the Vatican to its very core, that it caused the Vatican to “instantly” grant overwhelming power and independence to the Templar Order within less than one year.

The core foundational principle of the Templar Order, that archaeology of the Ancient Egyptian Priesthood is a Holy and Sacred Mission, essential to preserving the underlying foundations of Christianity, has been recognized by the Vatican:

Pope Benedict XIV, a Templar revivalist, who restored secret “Templar Lines” of Apostolic Succession and reinstated them in the Vatican (during 1726-1740 AD), first established the Academy of Antiquities in 1740 AD to explore the ancient origins of Christianity.

This became the Academy of Archaeology in 1810 AD, which Pope Pius VIII granted the status of “Pontifical Academy” in 1829 AD, for “the study of archaeology and the history of ancient and medieval art”. [35]

Pope Gregory XVI founded the “Gregorian Egyptian Museum” inside the Vatican itself in 1839 AD, preserving many papyrus scrolls including the Egyptian “Book of the Dead”, as well as mummies and sarcophagi bearing priestly inscriptions. The collection focuses on ancient artifacts which trace the roots of early “Coptic” (Egyptian) Christianity back to Pharaonic times.

The Vatican Museums Management stated that “The Pope’s interest in Egypt was connected with the fundamental role attributed to this country by the Sacred Scripture in the History of Salvation.” This confirms reports of Church historians, that the Vatican Egyptology museum was intended to help Catholics increase their understanding of the Bible through archaeology. [36]

Pope Pius IX founded the Pontifical Commission of Sacred Archaeology in 1852 AD, which manages the Pontifical Academy of Archaeology, and is dedicated to “sites of Christian antiquarian interest… safeguarding the objects found during such excavations” [37].

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

This strategic establishment ensured that the Templar Order would always have its own sovereign authorities, allowing it to remain independent from the Vatican and from all other kingdoms, thus making all later grants of authorities from the Vatican optional and additional.

Baldwin II Granting the Temple to Hugues & Gaudefroy with Patriarch Warmund (13th c.) in manuscript ‘Histoire d’Outre-Mer’ by Guillaume de Tyr (Detail)

The prominent 19th century British Barrister and historian, Charles Addison, documented that the Templar Order was founded as follows:

“Nine Noble Knights formed a holy brotherhood in arms, and entered into a solemn pact”, inspired by “the religious and military fervour of the day, and animated by the sacredness of the cause to which they had devoted their swords”.

King Baldwin II of Jerusalem then “granted them a place of habitation within the sacred inclosure of the Temple on Mount Moriah”. [38]

As confirmed by 20th century encyclopedias, the historical record establishes that “Baldwin II, King of Jerusalem, gave the Knights Templars quarters in his palace, built on the site of Solomon’s Temple.” [39]

King Baldwin II granting the founding Knights Templar residence and headquarters in his Royal Palace in 1118 AD, for access to the Temple of Solomon, evidences a relationship of Royal Patronage.

Vatican records state that “Hughes de Payens… and eight companions bound themselves by a perpetual vow, taken in the presence of the Patriarch of Jerusalem”, thereby confirming that the Templar Order was formed directly under Royal Patronage of the Kingdom of Jerusalem [40].

The 12th century chronicler Archbishop William of Tyre documented that in 1119 AD, King Baldwin II and Patriarch Warmund officially gave both Royal Patronage and Ecclesiastical Patronage of the Kingdom of Jerusalem to the Templars as an Order of Chivalry:

“The Lord King and his noblemen and also the Lord Patriarch [of Jerusalem] and the prelates of the Church gave them benefices from their domains… some in perpetuity.” [41]

The fact of Royal Patronage of the Templars exclusively under the Kingdom of Jerusalem was further confirmed by other 12th century chroniclers:

“The King came to them and gave them land and castles and towns… the King succeeded in persuading the [Vatican’s] Prior of the Sepulchre to release them from obedience… and they left”. [42]

Customary law requires either Royal or Ecclesiastical Patronage for legitimacy of an Order of Chivalry. The King arranging independence from the Vatican Order of the Holy Sepulchre thus evidences that the Templar Order was transferred to the Sovereign Patronage of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem granting special status of the Knights Templar in 1120 AD, evidences an elevation of the Templar Order to possessing full sovereignty in its own right.

Archbishop William of Tyre further documented that the official Royal Patronage by King Baldwin II, and also Ecclesiastical Patronage by Patriarch Warmund, was again reconfirmed at the Council of Nablus in 1120 AD, and actually elevated to full Sovereign Protection of the Templar Order exclusively under the Kingdom of Jerusalem. [43] [44] [45] [46] [47] [48]

In customary international law, “Sovereign Protection” actually means a full grant of permanent sovereignty with independence, making the institution a Sovereign Order of Chivalry in perpetuity.

University historians generally recognize that the founding authority of the Templar Grand Mastery was the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and also indirectly confirm that the Order held full Sovereign Protection, by establishing that the Templars did not answer to any Kings:

“From this time all masters were leading political and military figures in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. … Although the Templars were not directly responsible to any secular monarch… at least seven of the twenty-two masters were appointed by direct secular intervention.” [49]

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

British Barristers of the 19th century documented the rule of customary law that in an elective monarchy, Crown Regency power is vested in the High Court or Parliament: “It is unquestionably in the [authority of] … parliament, to defeat [a] hereditary right… and vest the [crown] in any one else.” [50]

For the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Crown Regency body for determining Royal Succession was the “High Court” (‘Haute Cour’), also called the Royal Council (‘Curia Regis’) or Parliament (‘Parlement’), which combined legislative and judiciary powers.

In 1120 AD the High Court of Jerusalem included the co-founding Templar Patron Count Fulk d’Anjou who had directly and fully joined the Templar Order that same year (later King of Jerusalem in 1131 AD) [51].

In 1148 AD the Court included the 2nd Templar Grand Master Robert de Crayon, “many others” of the Knights Templar, and the Angevin King Louis VII of France [52].

University historians documented that for many decades “during the 1130’s and 1140’s” and thereafter, “all masters” of the Templar Grand Mastery “were leading political and military figures in the Kingdom of Jerusalem” [53].

Vatican records witnessed that the Templar Order, “possessing power equal to that of the leading temporal sovereigns… assumed the right to direct the… government of the Kingdom of Jerusalem” [54].

This special role of the Knights Templar, serving as Judges of the High Court with Crown Regency power, appears to have been planned from its inception:

The Temple Rule of 1129 AD, which was actually based upon its earlier foundations from 1118 AD and developed by Saint Bernard with Hughes de Payens from 1120 AD [55], dedicates the Order to “the love of Justice which constitutes its duties” (Rules 2, 47), to “govern Justly” (Rule 57), and commands all Templars “for the love of Truth… to Judge the matter” by serving as Judges over disputes whenever requested (Rule 59) [56].

Serving as the High Court is the best possible strategic role to most effectively serve as Defenders of a Kingdom, because nobody can legitimately claim or assume the throne, without Judges of the High Court approving it as lawful. This establishes a real and practical deterrent, defending the Kingdom against legalistic hostile takeovers, false or coercive claims to the throne, or even aggression such as assassinations or military conquest.

The Temple Rule evidences that the Order was authorized to serve in this same role of the High Court, to be Defenders of multiple kingdoms: It declares a founding mission “to serve in chivalry with the sovereign King” (Rule 1). The specific use of the word “with” (thus not “under” any King), necessarily means that the Templar Order remained free to work with other kingdoms. [57]

By this precedent of the Templar Order serving as the High Court of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, throughout the Middle Ages, the Crown Regency bodies of kingdoms increasingly upheld the Templar principles of meritocracy, such that Royal Succession could be acquired “by office” as election for merit, or otherwise “by letters” as appointment for merit [58].

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Under customary international law, a Kingdom or Principality retains its own Crown and sovereignty, even if it loses its territory, and continues to hold governmental and diplomatic status, regardless of whether it has territories or not in the future, as an “independent non-territorial power” [60].

In modern conventional international law, a sovereign non-territorial state holds the legal status of a “sovereign subject of international law”, giving it full capacity of diplomatic relations regardless of territory [61] [62].

As a result, once an Order of Chivalry becomes sovereign by grant of Sovereign Protection, and has governed any Principality as its former territory, it thereafter retains permanent status as a “Non-Territorial Principality”, possessing its own inherent “Crown” authority.

This legal fact is the basis for a related rule of customary law, that every Grand Master of a Sovereign Order of Chivalry which is a Non-Territorial Principality, by one’s election, is thereby created a Prince in legitimate international Nobility peerage, designated as a “Prince of the Order”.

The resulting “Prince Grand Master” title is confirmed by other legal precedents proven in the historical record: This same rule continues to be applied to the Order of Malta from ca. 1099 AD, and to the Teutonic Order as a branch of the Templar Order since its first Principality from 1309 AD.

After the Templar Order became a Principality in 1129 AD, only 10 years later in 1139 AD, the Vatican recognized this rule of customary law making every future Grand Master a Prince, in the Papal Bull Omne Datum Optimum granting additional Sovereign Protection: It confirmed the sovereignty of every Templar “Grand Master” as “head and ruler” of its “Princely House [principali domo]”, thus a Prince. [63]

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Under customary law and Canon law, such Ecclesiastical Sovereignty would necessarily flow from its own unique Templar Priesthood, as the Ancient Priesthood which it recovered from the Temple of Solomon.

Recognition of this legal and canonical fact by the Kingdom of Jerusalem apparently established a major precedent, influencing the Vatican to acknowledge that status and recognize the same.

Only 10 years later, in 1129 AD, the Vatican recognized the inherent sovereignty of the Templar Priesthood, by ratifying the Temple Rule as a Papal Decree granting additional Sovereign Patronage:

It describes the Templars under the Grand Master as “Disciples” (Rule 7), using a rare Old Latin term mentioning the “Pontificate of the Temple of Solomon” (Rule 8), describing its Ecclesiastical Sovereignty as “divine service… dressed with the crown” (Rule 9). [65]

Only 20 years later, in 1139 AD, the Vatican more specifically recognized independent Ecclesiastical Sovereignty of the Templar Priesthood, confirming that it derived from recovering the Ancient Priesthood from the Temple of Solomon, in the Papal Bull Omne Datum Optimum granting additional Sovereign Protection:

“Your own religion [vestra religio]… [was] established in your house [the Temple of Solomon]… whereas the house itself [domus ipsa] is… the source and origin [fons et origo] of your Holy institution and Order… [a] Princely house [principali domo]… We [thus] recognize that authority [concedimus facultatem, literally ‘concede the capacity’]”.

For those reasons, it further declared: “The customs for observance of your [Templar] religion and service… shall not be infringed… subject to no person outside your Order… We command… that Ordinations by your [Templar] Clergy… [must] be received [accepted]” by Vatican Bishops. [66]

About 40 years later, by ca. 1150 AD, the Vatican further recognized and reconfirmed Ecclesiastical Sovereignty of the Templar Priesthood, by ratifying amendments to the Temple Rule as a Papal Bull:

It commands that only “Templar Chaplains should hear the confessions” and “No Templar should make confession to anyone else” (Rule 269) [67]. Since then, the Vatican has always confirmed that the Templar Order had independent “Chaplains, who alone were vested with” exclusive authority to administer all “sacerdotal orders [sacraments], to minister to the spiritual needs of the Order” [68].

Therefore, in addition to the Templar Order holding its own sovereign status as a Non-Territorial Principality, making its secular statehood independent from the Vatican, it was also officially recognized as holding its own inherent Ecclesiastical Sovereignty from the Ancient Priesthood, making it canonically and religiously independent from the Vatican.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

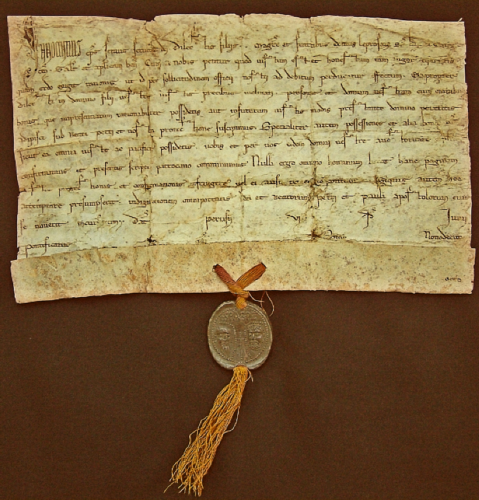

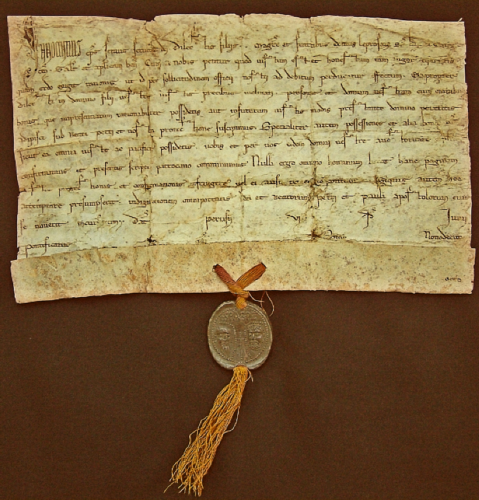

Pope Innocent II issued the Papal Bull Omne Datum Optimum (“Every Good Gift”) in 1139 AD, named after the scripture passage in James 1:17-18 (“Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, and cometh down from the Father [God]… with the word of Truth”.)

‘Omne Datum Optimum’ of 1139 AD (Cover) issued by Pope Innocent II granting Sovereignty to Templar Order as Principality

This monumental Papal Bull granted additional full Sovereign Protection to the Templar Order, recognizing its own inherent permanent sovereignty of statehood with independence. As Pope Innocent II rose to the Papacy despite adversity, promoted and supported by the Templar Patron Saint Bernard de Clairvaux, this Papal Bull evidences that independent sovereignty had always been part of the original plan for the Order [69].

It grants to the “Order of the Knighthood of the Temple… and [its] successors… both present and future in perpetuity… the Protection and Tutelage of the Holy See [Vatican] for all time to come.” [70]

The word “Protection”, and the full phrase “Tutela Protection”, is a special term of Canon law as customary international law, meaning an irrevocable grant of permanent sovereignty with independence.

University scholars confirm that this key phrase officially enacted “papal letters of protection” in the legal sense, which thus “laid the jurisdictional foundation of the Order’s independence”, by granting recognition of full sovereignty as “the most sweeping of their privileges”. [71]

Confirming the sovereign statehood of the Templar Order as a Principality, Omne Datum recognized it as a “Princely house [principali domo]… [with] dependencies… forever the head and ruler of all those places belonging to it.” Confirming sovereign diplomatic status and immunities of the Order, it declared that its authorities “may not be infringed nor diminished by any ecclesiastical or secular person.” [72]

Proving conclusively that this Vatican grant of Sovereign Protection is permanent and absolutely irrevocable, the ending section unequivocally declares: “If anyone, with the knowledge of this our decree, rashly attempts to act against it… he shall lose the dignity of his power and honor”, and shall be “accused of the perpetrated injustice before the divine court… subject to severe vengeance at final judgment.” [73]

This massively historic landmark Papal Bull, most officially and publicly proving the independent sovereignty the Templar Order, has been (incredibly) overlooked, as if suppressed:

Most modern ‘history books’ typically dismiss Omne Datum as merely “exempting” the Templars from paying tithes to the Church or taxes to Kings, if they mention it at all. Such superficial and indirect references fail to disclose the actual reason why the Order was “exempt” – precisely because it was granted full permanent and irrevocable Sovereign Protection, specifically by official recognition of its own independent sovereignty of statehood in its own right, as a Non-Territorial Principality with diplomatic status.

The grant of full Sovereign Protection by the Papal Bull Omne Datum Optimum of 1139 AD, in particular the resulting diplomatic status, is confirmed by two later supporting Papal Bulls:

In 1144 AD, Pope Celestine II issued the Papal Bull Milites Templi (“Knights of the Temple”), confirming the diplomatic status, specifically as the traditional diplomatic privileges and immunities, of the Templar Order:

It declared, for the “Knights of the Temple”, that “we instruct” all Vatican Clergy “to maintain their persons and goods, and not permit any damage or injury to be imposed upon them”. [74]

In 1145 AD, Pope Eugenius III, the first Cistercian to become Pope who was mentored by the Templar Patron Saint Bernard at the Monastery of Clairvaux [75] [76], issued the Papal Bull Militia Dei (“Knighthood of God”), further confirming the diplomatic status and immunities of the Templar Order, specifically emphasizing its Ecclesiastical Sovereignty:

It declared that the “Knighthood of the Temple” has “the right to recruit anywhere priests”, and instructs “the Archbishops” to “not impede them or permit them to be impeded in the building of their places of prayer.” [77]

Legal scholars confirm that “Sovereign Protection” is a legal term of customary law, meaning a grant of permanent independent sovereignty [78][79].

Nobiliary experts on chivalric law confirm that this “Sovereign Protection” is what makes an Order “an independent non-territorial power” [80] [81] [82].

University scholars confirm that “Letters of Protection” create “the Order’s independence” [83], such that the sovereign Order does not answer to any kingdoms [84].

Official Vatican records consistently witnessed that Orders of Chivalry granted Sovereign Protection did in fact exercise full sovereign status of independent statehood as a Non-Territorial (international) Principality in diplomatic relations:

Such Orders were “Quite independent… possessing power equal to that of the leading temporal sovereigns” [85].

“Moreover, the [Sovereign] Orders of religious knighthood, [including] the Templars… formed regular powers, equally independent of Church and State. … the Pope [and] the King could not interfere in their temporal affairs, and each of the three Orders had its own army and exercised the right of concluding treaties… [Even] royal authority was restricted to rather narrow limits by these various powers” [86].

Therefore, in the proven “lost” history (now “found” and restored) of its true foundations, the Templar Order began as a Holy Mission to recover the Ancient Priesthood from the Temple of Solomon, under Royal Patronage, and quickly earned full Sovereign Protection, becoming a Non-Territorial (international) Principality, possessing its own independent Crown authority among Kingdoms.

Learn about the French Persecution suppressing the Order.

Learn about the Templar Survival Lineage into the modern era.

Learn about Templar Legal Succession continuing sovereignty.

[1] Plato, Phaedrus (370 BC), “Η αρχή της σοφίας είναι ο καθορισμός των όρων” (“The beginning of wisdom is the definition of terms”), quoting Socrates teaching the principle of good rhetoric, that a speaker must define terminology at the beginning of a speech; Aristotle, Metaphysics (ca. 350 BC), confirms that Socrates was occupied with the “search for universal definitions”.

[2] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rules 2, 14, 57.

[3] Frank Sanello, The Knights Templars: God’s Warriors, the Devil’s Bankers, Taylor Trade Publishing, Oxford (2005), pp.5-6, 7.

[4] Piers Paul Read, The Templars (1999), Phoenix Press, London (2001), pp.91-92.

[5] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rule 121.

[6] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rule 9, Rule 274.

[7] The Vatican, The Code of Canon Law: Apostolic Constitution, Second Ecumenical Council (“Vatican II”), Enacted (1965), Amended and ratified by Pope John Paul II, Holy See of Rome (1983); Canon 278, §3; Canon 285, §§1-2.

[8] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rule 678.

[9] Michael Lamy, Les Templiers: Ces Grand Seigneurs aux Blancs Manteaux, Auberon (1994), Bordeaux (1997), p.28.

[10] Alan Butler & Stephen Dafoe, The Warriors and Bankers, Lewis Masonic, Surrey, England (2006), p.20.

[11] Karl Heinrich Rengstorf, Hirbet Qumran and the Problem of the Library of the Dead Sea Caves, German edition (1960), Translated by J.R. Wilkie, Leiden Press, Brill (1963).

[12] Titus Flavius Josephus, Jewish War, Rome (78 AD); Translation by William Whiston (1736), Loeb Classical Library (1926), Volume II, Book 5, pp.212, 217.

[13] Charles G. Addison, The History of the Knights Templar (1842), p.6, citing the document De Aedificiis by the 5th century Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea as “Procopius de Oedificiis Justiniani, Lib. 5.”

[14] Charles G. Addison, The History of the Knights Templar (1842), pp.4-5, citing a Vatican document by the 13th century Pope Urban IV (Jacques Pantaleon, 1195-1264), the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, as “Pantaleon, Lib. iii. p. 82.”

[15] Old Testament, Authorized King James Version (AKJV), Cambridge University Press (1990), I Kings 4:21.

[16] Charles Van der Pool, The Apostolic Bible Polyglot: Greek-English Interlinear, 2nd Edition, The Apostolic Press, Newport, Oregon (2013), I Kings 4:21.

[17] NAS Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, The Lockman Foundation (1981), Greek Dictionary: “Heos”, “Horion”.

[18] Hector Avalos, How Archaeology Killed Biblical History, Lecture Video, Minnesota Atheists Conference, USA (October 21, 2007), Part 1, “By 900 BC… Solomon had a kingdom that stretched from Egypt to Iraq” (at 12:30 min); Hector Avalos is a Ph.D. in Biblical Studies from Harvard University.

[19] Hiram Ralph Burton, The Origin History and Object of the Alfalfa Club, Washington DC (1917), p.7; Burton was a lawyer from Georgetown University Law School, and Special Investigator for multiple US Senate committees.

[20] Prof. Arthur Samuel Peake (Editor), A Commentary on the Bible, T.C. & E.C. Jack, Ltd., London (1920), Ezekiel 8:10-11; Dr. Peake was Professor of Biblical Exegesis at University of Manchester, a Master of Arts and Doctor of Divinity.

[21] Titus Flavius Josephus, Jewish War, Rome (78 AD); Translation by William Whiston (1736), Loeb Classical Library (1926), Volume II; See pp.212, 217; The Temple contained decorations of “mystical interpretation… a kind of image of the universe… all that was mystical in the heavens… [and] signs, representing living creatures.” (Book 5, Chapter 5, Part 4) Other symbols “signified the circle of the Zodiack” (Book 5, Chapter 5, Part 5); This is connected with the “Zodiak” of Dendera Temple, original preserved in the Louvre museum, replaced by a replica at the Dendera site in Egypt.

[22] Titus Flavius Josephus, The Life of Flavius Josephus, Rome (ca. 96 AD); Translation by William Whiston (1736), Loeb Classical Library (1926), Volume I; See p.65; The Temple replica rebuilt by King Herod also “had the figures of living creatures in it” (Part 12).

[23] Saint Augustine, Retract I, XIII, 3 (ca. 418 AD); Eugene TeSelle, Augustine the Theologian (1970), reprinted London (2002), p.343.

[24] Saint Jerome, Epistola 195 (418 AD); Eugene TeSelle, Augustine the Theologian (1970), reprinted London (2002), p.343.

[25] Sir Alan G. Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar: The Study of Hieroglyphs, Ashmolean Museum of Oxford University, Griffith Institute, Oxford (1927), “Aten” (Spirit of Sun Rays = Christian “Holy Spirit” or “Power of God”), List of Hieroglyphic Signs (pp.438 et seq.): “Aten”, N8; “Ka” (“Spirit”, Hands used on the Aten rays), D28.

[26] Donald B. Redford, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, The American University in Cairo Press (2001), Vol.1, “Aten”, p.157.

[27] Sir Alan G. Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar: The Study of Hieroglyphs, Ashmolean Museum of Oxford University, Griffith Institute, Oxford (1927), “Neterwoo” (“Gods” = Christian “Angels” and “Saints”), List of Hieroglyphic Signs (pp.438 et seq.): “NTRW” (Holies, such as Angels or Saints, mistranslated as “Gods”), R8-R8-R8, (Prophets speaking Holiness) R8-N35-M6-M6-M6; “HM NTR” (“Prophet” as a Saint), R8-U36; “NTR” (Holiness as Saintly: flag), R8, (Astral as Angelic: flag-star), R8-N14; “TRY” (Holiness or Divinity, as “high priest”), D1-Q3-Z4, T8, D1-Q3; “NIWTYW” (People, “citizens”, as “of” or “from” the Temple complex) O49-X1-G4-A1-Z2; “DWT NTR” (“Netherworld”: circled star), N15.

[28] Patrick Boylan, Thoth or the Hermes of Egypt: A Study of Some Aspects of Theological Thought in Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press (1922), pp.166-168.

[29] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1908), Volume 4, “Councils”, “III. Historical Sketch of Ecumenical Councils”, Part 7, p.425; Describing the Second Council of Nicea in 787 AD.

[30] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1911), Volume 11, “Nicaea, Councils of”, “II. Second Council of Nicaea”, p.46.

[31] Keith Laidler, The Head of God: The Lost Treasure of the Templars, 1st Edition, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London (1998), p.177.

[32] Piers Paul Read, The Templars: The Dramatic History of the Knights Templar, the Most Powerful Military Order of the Crusades, 1st Edition, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London (1999), Phoenix Press, London (2001), Orion Publishing Group, London (2012), p.305.

[33] Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.2.

[34] Idries Shaw, The Sufis (1964), republished by Anchor Press (1971); “Idries Shaw” is the Sufi Master and historian Sayed Idries el-Hashimi (1924-1996).

[35] The Vatican, Pontifical Roman Academy of Archaeology, Pontifical Council for Culture, Rome, Online: Theologia.va (July 2012).

[36] The Vatican, Gregorian Egyptian Museum, Vatican Museums Management (museivaticani.va), Statement (2003), Republished in “Sections” topic (2007): “Pope Gregory XVI had the Gregorian Egyptian Museum founded in 1839. … The Popes’ interest in Egypt was connected with the fundamental role attributed to this country by the Sacred Scripture in the History of Salvation. … The last two rooms house finds from ancient Mesopotamia and from Syria-Palestine.”

[37] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 1, “Archaeology: Commission of Sacred Archaeology”.

[38] Charles G. Addison, The History of the Knights Templar (1842), pp.4-5, citing a Vatican document by the 13th century Pope Urban IV (Jacques Pantaleon, 1195-1264), the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, as “Pantaleon, Lib. iii. p. 82.”

[39] Collier’s Encyclopedia, Thomson Gale (1985), 1985 Edition, Macmillan Library Reference (1990), “Knights Templars”.

[40] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 14, “Templars, Knights”, Part 1, “Their Humble Beginning”, p.493.

[41] William of Tyre, Historia Rerum in Partibus Transmarinis Gestarum (ca. 1172 AD), XII, 7, Patrologia Latina, 201, 526-27, Translated by James Brundage, The Crusades: A Documentary History, Marquette University Press, Milwaukee (1962), pp.70-73.

[42] Ernoul & Bernard, Chronique d’Ernoul et de Bernard le Tresorier (ca. 1188), Ed. L. de Mas Latrie, Paris (1871), Chapter 2, pp.7-8.

[43] Kingdom of Jerusalem, Council of Nablus: Concordat of Canons (1120 AD), established by Patriarch Warmund and Kind Baldwin II of the Kingdom of Jerusalem; Preserved in the Sidon Manuscript, Vatican Library, MS Vat. Lat. 1345: “Introduction to Canons”; Canon 20.

[44] Hans E. Mayer, The Concordat of Nablus, The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Cambridge University Press, No. 33 (October 1982), pp.531-533, 541-542.

[45] Dominic Selwood, Quidem Autem Dubitaverunt: The Saint, the Sinner, the Temple; Published in: M. Balard (Editor), Autour de la Première Croisade, Publications de la Sorbonne, Paris (1996), pp.221-230.

[46] Dominic Selwood, Knights Templar III: Birth of the Order (2013), historian for Daily Telegraph of London, article.

[47] Malcolm Barber, The Trial of the Templars, Cambridge University Press (1978), p.5, p.8.

[48] Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.5.

[49] Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.5.

[50] Herbert Broom & Edward Hadley, Commentaries on the Laws of England, Parsons Law Book Publisher, Albany New York (1875), Volume 1, Book 1: “The Rights of Persons”, Chapter 3: “The Sovereign”, Point 3, p.156.

[51] M. Chibnall, The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1978), Volume 6, pp.308-311.

[52] High Court of Jerusalem, Decrees of the Council of Acre, Palmarea (24 June 1148); Attended by the Knights Templar, and Angevin Templar Nobility; Archbishop William II of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea (12th century), translated in: E.A. Babock & A.C. Crey, Columbia University Press (1943).

[53] Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.5.

[54] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 14, “Templars, Knights”, Part 2, “Their Marvellous Growth”, pp.493-494.

[55] Judith M. Upton-Ward, The Rule of the Templars, Woodbridge, The Boydell Press (1992), p.11; Dissertation for Master of Philosophy at Reading University.

[56] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rules 2, 47, 57, 59.

[57] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rule 1.

[58] François Velde, Nobility and Titles in France, Heraldica (1996), updated (2003), “History of Nobility: Acquisition of Nobility”.

[59] Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, Volume 2: “The Kingdom of Jerusalem”, Cambridge University Press (1952), pp.212-213, 222-224.

[60] International Commission for Orders of Chivalry (ICOC), Report of the Commission Internationale Permanente d’Études des Ordres de Chevalerie, “Registre des Ordres de Chivalerie”, The Armorial, Edinburgh (1978), Gryfons Publishers, USA (1996), including: Principles Involved in Assessing the Validity of Orders of Chivalry (1963), Principle 2, Principle 3, Principle 6.

[61] Rebecca Wallace, International Law: A Student Introduction, 2nd Edition, Sweet & Maxwell (1986).

[62] Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969), Preamble, Article 3.

[63] Pope Innocent II, Omne Datum Optimum “Every Good Gift” (29 March 1139); Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), pp.59-64.

[64] Ernoul & Bernard, Chronique d’Ernoul et de Bernard le Tresorier (ca. 1188), Ed. L. de Mas Latrie, Paris (1871), Chapter 2, pp.7-8.

[65] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rules 7, 8, 9; In Rule 8, Old Latin “Patriarchae Ierosolimitarum”: “Iero” means “Priesthood” or “Temple” (from Greek “Hieros” meaning “sacred” and “Hieron” meaning “temple”), “Solomin” means the Biblical “Solomon”, and “Imitarum” means “representation”; Thus “Solimitarum” means “representing Solomon”, and “Ierosolimitarum” means the “Temple Representing Solomon”; Therefore, the “Patriarchate” of the independent Ancient Priesthood from the Temple of Solomon, specifically means a “Pontificate”.

[66] Pope Innocent II, Omne Datum Optimum “Every Good Gift” (29 March 1139); Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), pp.59-64.

[67] Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard, Rule 269.

[68] The Vatican, Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 14, “Templars, Knights”, Part 1, “Their Humble Beginning”, p.493.

[69] Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.8.

[70] Pope Innocent II, Omne Datum Optimum “Every Good Gift” (29 March 1139); Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), pp.59-64.

[71] Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.8.

[72] Pope Innocent II, Omne Datum Optimum (29 March 1139), translated in: Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), pp.59-64; Word “Princely” in the original Latin, mistranslated as “principal” in modern English by universities.

[73] Pope Innocent II, Omne Datum Optimum (29 March 1139), translated in: Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.64.

[74] Pope Celestine II, Milites Templi, “Knights of the Temple” (5 January 1144), translated in: Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.8, pp.64-65.

[75] Michael Horn, Studien zur Geschichte Papst Eugens III (1145-1153), Peter Lang Verlag (1992), pp.36-40, pp.42-45.

[76] Saint Bernard de Clairvaux, On Consideration, Letter to Pope Eugene III, Translated in: George Lewis, Saint Bernard: On Consideration, Oxford Library of Translations, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1908).

[77] Pope Eugenius III, Militia Dei, “Knighthood of God” (7 April 1145), translated in: Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.8, pp.65-66.

[78] Hans J. Hoegen Dijkhof, Hendrik Johannes, The Legitimacy of Orders of St. John: A Historical and Legal Analysis and Case Study of a Para-religious Phenomenon, Hoegen Dijkhof Advocaten, Universiteit Leiden (2006), p.36; “Sovereign Protection… In that case the Order involved… [can] dispose over the necessary Fons Honorum”.

[79] Hans J. Hoegen Dijkhof, Hendrik Johannes, The Legitimacy of Orders of St. John: A Historical and Legal Analysis and Case Study of a Para-religious Phenomenon, Hoegen Dijkhof Advocaten, Universiteit Leiden (2006), p.423; “a Sovereign is… providing his Protection to such Order… [which is] receiving Protection and is deriving the Fons Honorum from the Protection awarded”.

[80] International Commission for Orders of Chivalry (ICOC), Report of the Commission Internationale Permanente d’Études des Ordres de Chevalerie, “Registre des Ordres de Chivalerie”, The Armorial, Edinburgh (1978), Gryfons Publishers, USA (1996), including: Principles Involved in Assessing the Validity of Orders of Chivalry (1963), Principle 4: “independent Orders of Knighthood… must always stem from or be… under [Sovereign] Protection”.

[81] International Commission for Orders of Chivalry (ICOC), Report of the Commission Internationale Permanente d’Études des Ordres de Chevalerie, “Registre des Ordres de Chivalerie”, The Armorial, Edinburgh (1978), Gryfons Publishers, USA (1996), including: Principles Involved in Assessing the Validity of Orders of Chivalry (1963), Principle 6: A “Sovereign” Order having Protection thereby becomes “an independent non-territorial power”.

[82] Hans J. Hoegen Dijkhof, Hendrik Johannes, The Legitimacy of Orders of St. John: A Historical and Legal Analysis and Case Study of a Para-religious Phenomenon, Hoegen Dijkhof Advocaten, Universiteit Leiden (2006), p.292.

[83] Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.8; Confirming Sovereign Protection: “letters of protection” in the legal sense “laid the jurisdictional foundation of the Order’s independence”, by granting recognition of full sovereignty as “the most sweeping of their privileges”.

[84] Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.5; Confirming Sovereign Protection: “the Templars were not directly responsible to any secular monarch”.

[85] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 14, “Templars, Knights”, Part 2, “Their Marvellous Growth”, pp.493-494.

[86] The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1911), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 8, “Jerusalem”, p.363.

You cannot copy content of this page

Javascript not detected. Javascript required for this site to function. Please enable it in your browser settings and refresh this page.