The Knights Templar were the “Law Givers” of the Magna Carta, the first codified declaration of People’s Rights, as the backbone of Common Law, and the foundation of all modern Civil Rights and Human Rights under the Rule of Law. The Templar Order established, promoted and enforced the Magna Carta, as a priority strategic Templar mission. This was a major factor which provoked the French Persecution of the Templars.

Less than 50 years before the Magna Carta, the basis for English Common Law itself was initially developed by substantial legal reforms implemented by King Henry II (1133-1189 AD), of the Templar dynastic House of Anjou ((Paul Brand, Henry II and the Creation of the English Common Law, in Christopher Harper-Bill & Nicholas Vincent, Henry II: New Interpretations, Woodbridge UK, Boydell Press (2007), p.216.)). These sweeping reforms of the Royal Court system and its legal frameworks, backed by Knights Templar support, resulted in the very foundations of the Common Law system of jurisprudence.

Less than 50 years before the Magna Carta, the basis for English Common Law itself was initially developed by substantial legal reforms implemented by King Henry II (1133-1189 AD), of the Templar dynastic House of Anjou ((Paul Brand, Henry II and the Creation of the English Common Law, in Christopher Harper-Bill & Nicholas Vincent, Henry II: New Interpretations, Woodbridge UK, Boydell Press (2007), p.216.)). These sweeping reforms of the Royal Court system and its legal frameworks, backed by Knights Templar support, resulted in the very foundations of the Common Law system of jurisprudence.

When King Richard the Lionheart died in 1199 AD, he was succeeded by his brother King John (1166-1216 AD), who imposed excessive taxation on the English nobility, and confiscated and sold property of the Roman Catholic Church. These and other arbitrary abuses of power were mostly driven by the need to pay for failed foreign wars.

By 1214 AD, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, called on the Nobles to demand a charter of liberties from the King of England.

This resulted in the first time in history that a Common Law declaration of People’s Rights was imposed upon a monarch backed by armed force, causing the landmark Magna Carta to be enacted in 1215 AD.

Written in Roman Latin, its full title was Magna Carta Libertatum, literally the “Great Charter of Liberties”.

Historians generally identify the Magna Carta as an “Angevin” charter, specifically meaning of the Royal House of Anjou, the line of titled Counts of Anjou dating back to 870 AD. The 13th century Nobles of the House of Anjou, who were involved in creating the Magna Carta, dynastically descended directly from Count Fulk of Anjou, King of Jerusalem.

King Fulk was one of the first Noble Patrons backing the first two Grand Masters of the Templar Order since its establishment in 1118 AD ((Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), pp.5-6.)), and essentially served as the 10th founding Knight Templar from 1120 AD ((M. Chibnall, The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1978), Volume 6, pp.308-311.)).

The rebellious Nobles, who were direct signatories to the Magna Carta, are typically referred to in history books only generically as “Barons”. However, of those 25 English noblemen, actually 7 held the much higher title of Earl (Count), and 3 were heirs to an Earldom.

Significantly, 3 of the signatories to the charter were Nobles of Hereford, a major stronghold of Knights Templar loyalists, and the region of the first Templar headquarters Commandery at Garway. More importantly, one of the key parties of great influence among all the Nobles was Brother Aymeric, the Master (Prior) of the Knights Templar for England.

The occasional references in history books to the Magna Carta being “forced” upon King John rarely emphasize the actual level of organized armed military force that was necessarily involved, in order to impose such restrictions upon a ruling monarch. The military nature of this knightly force was so substantial, that it is recorded in history as the “First Barons’ War” (1215-1217 AD).

The primary and dominant organized armed force of militia in England, which was itself sovereign and thus independent from the Crown, was none other than the Knights Templar, the chivalric Order of Knights of the Temple.

The rebellion of Nobles was led by Robert Fitzwalter, a Templar Knight who was given the chivalric title of office “Marshal of the Army of God and Holy Church” specifically for the mission of establishing the Magna Carta. Further confirming that Fitzwalter was a Templar is the fact that he later fought in the Fifth Crusade (seeking to reacquire Templar sites and Holy relics). ((The Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Cambridge University Press (1911), “Fitzwalter, Robert”, p.449.))

When King John persisted in refusing the demands of the Nobles, in January 1215 AD Fitzwalter together with a group of Knights of nobility, all suited in full Templar battle armour with formal regalia of the Order of Knights of the Temple, held a key meeting with the King at Temple Church, the major headquarters Commandery of the Templar Order in London. ((Leslie Stephen, Dictionary of National Biography (1889), London, Smith Elder & Co. (1889), “Fitzwalter, Robert”, p.226)) ((Gabriel Ronay, The Tartar Khan’s Englishman, London, Cassel (1978), pp.38-40.))

Leading legal scholars in the Justice system of the United Kingdom are well aware that “many of the key moments in the two years leading up to the sealing of the Charter took place [in Temple Church]”. For this reason, Barristers (higher ranking lawyers) of the English legal system identify Temple Church as “the cradle of the Common Law.” ((Lord Judge Master of the Temple, The Greatest Knight, in: The Inner Temple Yearbook: 2013-2014, Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, pp.14-15.))

The exercise of force to establish Magna Carta culminated in the breakthrough event of 17 May 1215 AD, when Fitzwalter stormed the City of London leading the “Army of God”, in the name of the Templar Order.

Because the Templars already enjoyed wide popular and political support in London, the King’s soldiers essentially opened the gates to the city and let them in without much resistance other than some attempts from the Tower of London. ((Leslie Stephen, Dictionary of National Biography (1889), London, Smith Elder & Co. (1889), “Fitzwalter, Robert”, p.226 .))

Less than one month later on 15 June 1215 AD, the Knights Templar obtained King John’s seal accepting and ratifying the Magna Carta at Runnymede.

Even after its first enactment, the Magna Carta was repeatedly disregarded by King John, and the Church also rolled back some of its provisions several times, as a compromise to increase its own influence over the King.

Because Magna Carta was periodically limited by both the King and Church, and suspended by a small civil war against the Templar Nobles, it needed to be reissued and reasserted several times. This was accomplished primarily by the perseverance and backing of the Templar House of Anjou.

King Henry III (1207-1272 AD) was the heir of the Royal House of Anjou, a major Knights Templar dynasty carrying the original source of Royal Patronage of the Templar Order from the Kingdom of Jerusalem. When Henry III was 9 years old, the Angevins appointed William Marshall as his protector.

The Marshall Protectorate repeatedly reissued the Magna Carta from 1216 to 1225 AD, finally installing it as the basis for all future government of England. ((Danny Danziger & John Gillingham, 1215: The Year of Magna Carta, Hodder & Stoughton (2003), p.271.))

William Marshall is revered by the modern English legal profession as “one of the central figures” of the Magna Carta, and “one of the ultimate saviours of the Great Charter”.

For advancing Magna Carta rights, he was hailed by the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1219 AD as “the greatest Knight that ever lived.”

One of the effigies of the most famous Knights Templar, which lay in Temple Church, is that of William Marshall.

In the 1215 AD Magna Carta, his name is listed first among the non-clergy men noted as advising the King. When he re-issued the Charter in 1216 AD and 1217 AD to ensure its survival, he placed his own seal on it in Temple Church itself, where he is buried, and where his effigy still remains over 800 years later. ((Lord Judge Master of the Temple, The Greatest Knight, in: The Inner Temple Yearbook: 2013-2014, Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, pp.12-15.))

In 1297 AD, King Edward I (of the Templar House of Anjou) enacted Confirmatio Cartarum (Confirmation of Charters), reaffirming the Magna Carta. In 1300 AD he enacted the supplemental Articuli Super Cartas (Articles Upon the Charters), consisting of 20 additional Articles providing for stronger and more effective enforcement of the Magna Carta. ((William B. Robinson & Ronald H. Fritze, Historical Dictionary of Late Medieval England: 1272-1485, Greenwood Press (2002), “Articuli Super Cartas” at pp.34-35.))

Under mounting pressure from King Philip IV of France, who sought to expand his abusive practices of increasingly aggressive exercise of power, Pope Clement V annulled Confirmatio Cartarum in 1305 AD ((Sophia Menache, Clement V, Cambridge University Press (2002), p.253.)).

While the Magna Carta technically remained in force, that action politically weakened and undermined practical enforcement of its Rule of Law provisions which would limit the King’s ambitions.

The historical facts established above provide a revealing context for the events leading up to the French Persecution of the Knights Templar.

The Magna Carta – which was promoted, established and enforced by the Knights Templar – was a major factor leading to the French Persecution of the Templar Order in 1307 AD:

The Templar-backed reaffirmation of Magna Carta in 1297 AD, and issuance of new articles for its enforcement in 1300 AD, triggered a backlash pushed by the power-hungry secular King Philip IV of France in 1305 AD, blackmailing the Pope to annul the enforcement articles.

Within only a short two years thereafter, the King further coerced and abused the French Inquisition to persecute the Knights Templar with a full onslaught.

(The 2011 Hollywood movie “Ironclad” compellingly portrayed the importance of Magna Carta as a central mission of the Templar Order, and accurately expressed the level of dedication and sacrifice made by the Knights Templar, in their key role as the “Law Givers” of Magna Carta fighting to establish the Rule of Law.)

![]()

This made the Charter a core part of the most basic principles of jurisprudence, deeply embedded in the English Common Law, which has been the cornerstone of most national legal systems throughout Europe and most of the world. In fact, American colonial Courts considered Magna Carta to be the chief embodiment of Common Law in and of itself. ((Henry Elliot, Magna Carta Commemoration Essays (1917), H.D. Hazeltine, “The Influence of Magna Carta on American Constitutional Development in Malden”, p.194))

The Magna Carta was the primary foundation of all Common Law doctrines of People’s Rights, including the Rule of Law, Civil Rights, and Human Rights, and is also the foundation of modern Representative Democracy.

Rule of Law – The Magna Carta was the first codified declaration of law establishing that even the King is bound to observe the laws, prohibiting any claim to absolute or arbitrary rule by the monarchy. It was the first enactment of the principle of sovereignty of the Rule of Law itself, such that no ruler and no other government official can hold oneself above the law.

Civil Rights – The Magna Carta was the first charter in history to mandate specific guarantees of Civil Rights and common privileges, as well as protections of Freedom of Religion. This effectively set the legal precedent for a Bill of Rights to be enacted in all countries. This in turn laid the foundations of the principle of constitutional law internationally, as the binding recognition of all Civil Rights, as universal rights of God’s Law as Natural Law established as the Common Law, as “customary international law”.

Human Rights – Many principles derived from the original provisions of the Magna Carta have been codified into the modern framework of Conventions on Human Rights, which comprise the fundamental body of “conventional international law” which is binding upon all countries. The modern Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 is based upon 18th century models for Bills of Rights, which were derived from the core principles of the Magna Carta.

After it’s enactment, the subsequent implementation of the Magna Carta also greatly influenced the development of political representation by a Parliament. Thus, the charter is also attributed with being the primary foundation of Representative Democracy, upon the basis of individual liberties against arbitrary abuses of authority.

One major predecessor to the traditional institution of Parliament, as an early medieval form of Representative Democracy, is the Grand Mastery of the Knights Templar, since the foundation of the Order of Knights of the Temple in 1118 AD:

As evidenced by the Temple Rule of 1129 AD, the very concept of the Grand Mastery is that governance is not left to the Grand Master alone, but is balanced by a Sovereign Council of Grand Officers, who in turn represent the general population of all Knights and Dames of the Order (Rules 206-207) ((Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard: The “Grand Commander shall summon the majority of worthy Knights [and Dames]… who are officers and the most prominent… [as] thirteen electors” (Rules 206-207).)). The Grand Mastery has always been based upon Arthurian “Round Table” principles (Rules 18, 34, 46, 393, 412) ((Henri de Curzon, La Règle du Temple, La Société de L’Histoire de France, Paris (1886), in Librairie Renouard: “We command everyone to have the same” (Rule 18); “No person shall be elevated among you” (Rule 34); It is forbidden “to promote oneself gradually” (Rule 46); At Council meetings members take turns speaking, going around the tables (Rules 393, 412).)), where all members are ensured full and equal participation in governance through parliamentary representation.

The Templar Order itself was actually the “High Court” and “Royal Council” of the Kingdom of Jerusalem by ca. 1148 AD ((M. Chibnall, The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1978), Volume 6, pp.308-311; The High Court included the co-founding Templar Patron Count Fulk d’Anjou.)) ((High Court of Jerusalem, Decrees of the Council of Acre, Palmarea (24 June 1148); Attended by the Knights Templar, and Angevin Templar Nobility; Archbishop William II of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea (12th century), translated in: E.A. Babock & A.C. Crey, Columbia University Press (1943); The High Court in 1148 AD included the 2nd Templar Grand Master Robert de Craon, “many others” of the Knights Templar, and the Angevin King Louis VII of France.)) ((Malcolm Barber & Keith Bate, The Templars: Selected Sources, Manchester University Press (2002), p.5; “All masters” of the Templar Grand Mastery “were leading political and military figures in the Kingdom of Jerusalem”.)), thus serving as its Parliament, carrying even the Crown Regency authority to determine and establish Royal Succession ((The Vatican, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912), The Encyclopedia Press, New York (1913), Volume 14, “Templars, Knights”, Part 2, “Their Marvellous Growth”, pp.493-494; The Templar Order exercised “the right to direct the… government of the Kingdom of Jerusalem”.)).

This Templar governance is the major precedent of customary international law which was later adopted by the United Kingdom ca. 1701 AD to become a constitutional monarchy, considered a modern Democracy.

The Magna Carta also solidified the principles of codified Public Law, by which Civil Rights and Justice require that the general public have notice and transparent access to clear rules of law, as a protection against arbitrary abuses of power.

The Temple Rule of 1129 AD itself is one early precedent for the practice of codified Public Law, as a medieval form of the Rule of Law subject to the doctrines of Common Law: It is an earlier landmark charter, demonstrating the enactment of a communal law by democratic consultation of a representative council, by which publicly disclosed rules of law serve to implement practices of Civil Rights and Justice under Common Law.

The most famous provision of the Magna Carta is ‘Article 29’ of the 1297 AD version (originally ‘Clause 39’ of the 1215 AD version), which established the most fundamental doctrines of jurisprudence on the right to own private property, the right to a trial without delay (the basis for ‘habeas corpus’), the right to trial by one’s peers (the basis for a jury trial), and thus the absolute right of all citizens to Due Process of law, free from arbitrary interference by the government.

This clause required that: “No free man shall be arrested or imprisoned, or dispossessed of his Freehold [property], or Liberties… or in any other way destroyed… nor [to] condemn him, except by the lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the law of the land.”

The same clause also provides: “We will sell to no man, we will not deny or [delay] to any man, either Justice or Right.”

This prohibits charging or accepting money for any favourable judgment (i.e. bribery or burdensome litigation fees), prevents lawsuits and motions from being arbitrarily dismissed on technicalities, and excludes stalling or delay tactics by defendants or the State.

The original ‘Clause 61’ (of the 1215 AD version) created a Council of 25 Nobles who could overrule the King if he ever defied the rights in the charter, and could even seize his castles and property if they deemed necessary. This and many other provisions were not preserved in later versions. Nonetheless, this clause did establish the historical basis and legal precedent for the concept of “impeachment” of a Head of State by the Parliament.

The Lord Judge of Inner Temple Inn of Court in London summarized: “Through [the Magna Carta], the Common Law has penetrated the world. The ideas derived from it have underpinned all the great declarations of human rights. It is a universal document, continuing to have universal impact.”

Most importantly, it established “that the King himself was subject to the law, and that if he failed to abide by that understanding, he was not entitled to claim an obligation of loyalty. … To this day, all our rulers are subject to the law.” ((Lord Judge Master of the Temple, The Greatest Knight, in: The Inner Temple Yearbook: 2013-2014, Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, p.14.))

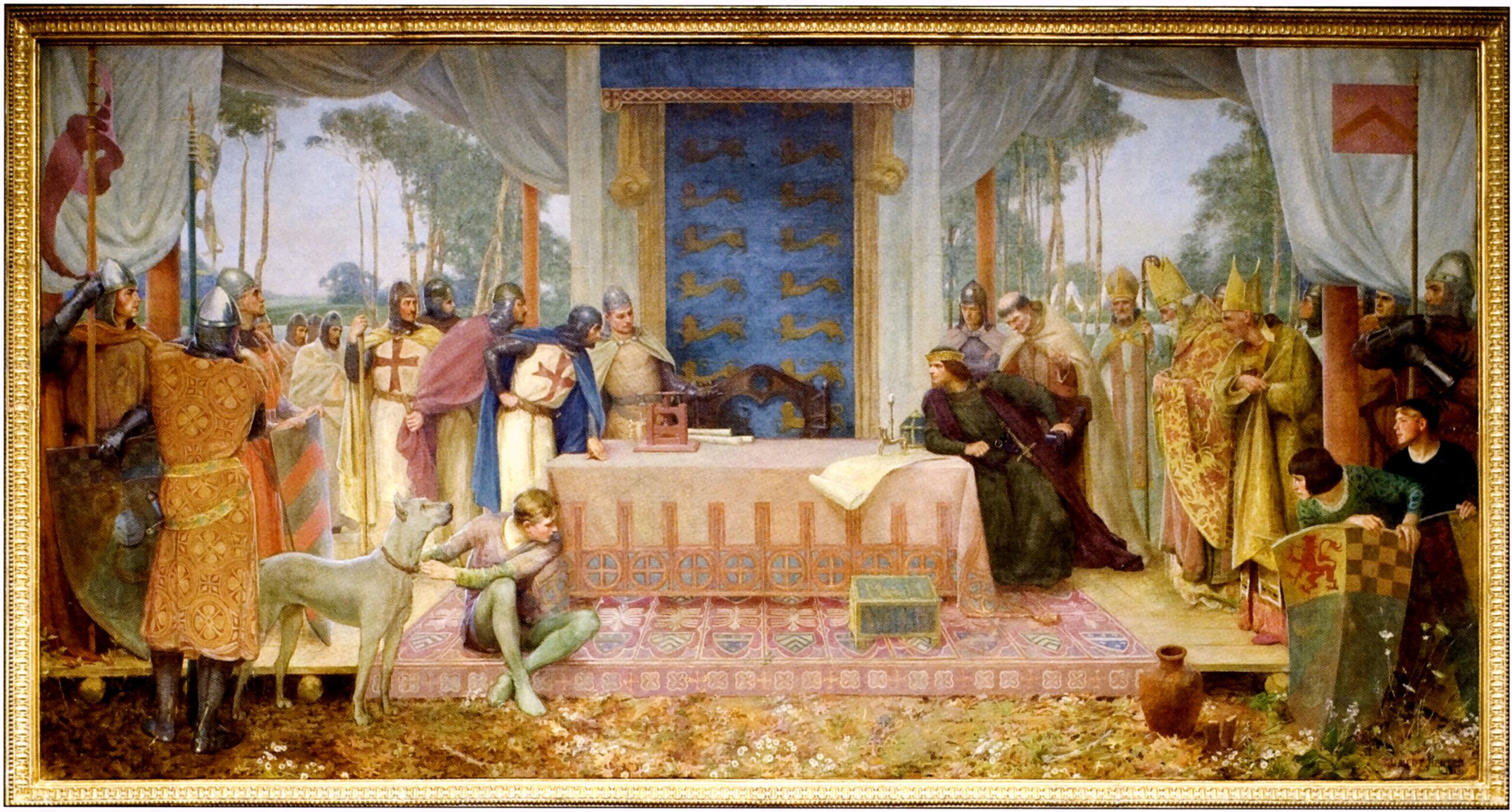

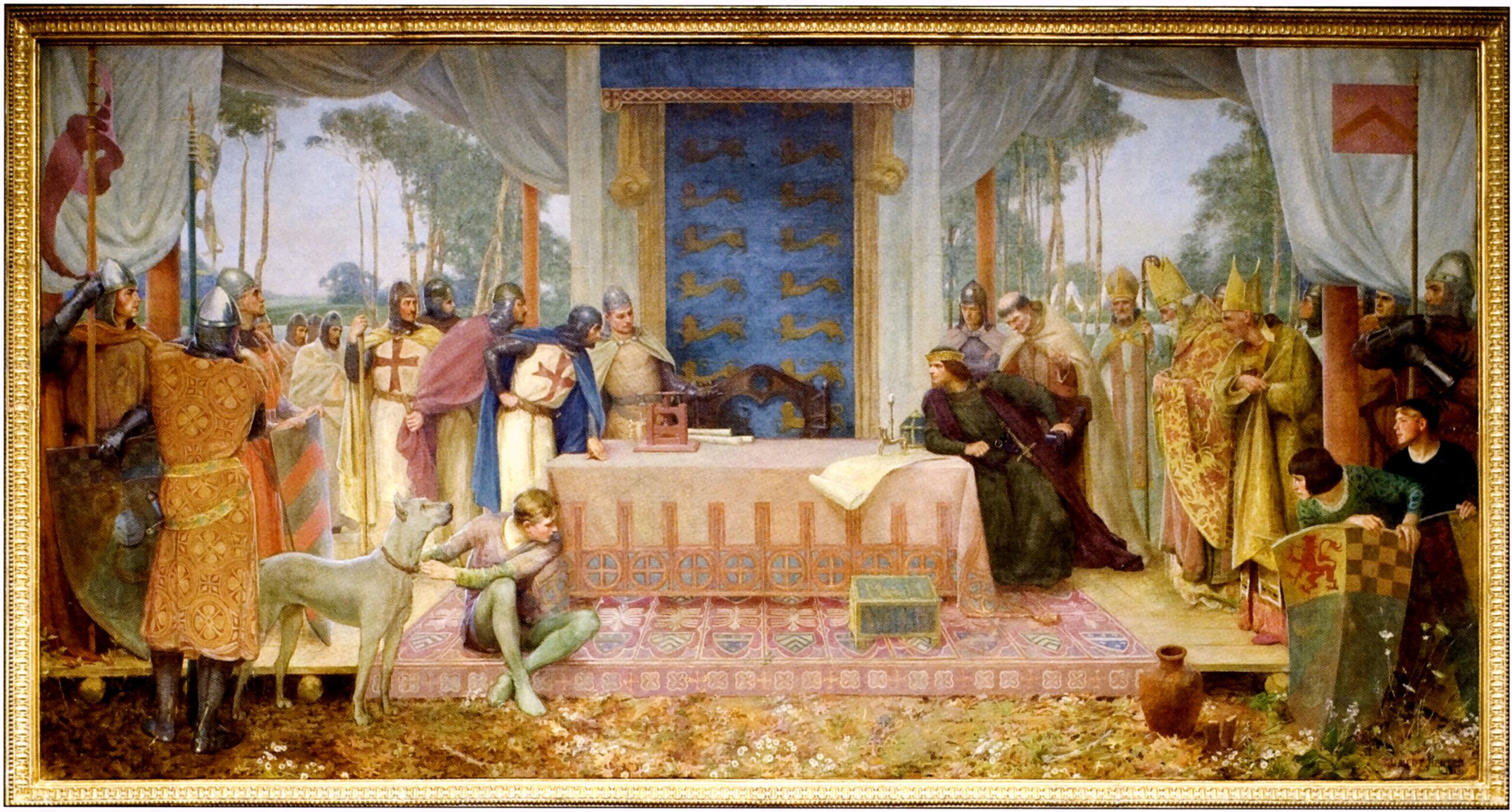

‘Templars Signing the Magna Carta’ by Albert Herter (ca. 1915) in Wisconsin Supreme Court Room

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Modern legal systems have developed a dominant system of “statutory law”, by legislation and administrative regulations, which increasingly undermines or even violates universal People’s Rights which are irrevocable in Common Law. Independent researchers consistently uncover evidence that the modern statutory system is driven by secret practices, which are used by corrupt factions to manipulate the legal system internationally.

As a result of this provable reality of an increasingly corrupt statutory legal system, many advocates of People’s Rights pursue various “Common Law” strategies for reclaiming fundamental rights.

Such strategies are typically based on theories of navigating the labyrinth of intricate legal complexities of the secret practices of the statutory system, seeking to reassert the lawful and rightful status of the individual in the jurisdiction of Common Law, which guarantees People’s Rights.

The popular trend of navigating secret legal complexities has increasingly caused much confusion, mistaking doctrines of Common Law which are easy to prove and can be directly enforced, with secret loopholes of secret rules which are hard to prove and cannot be enforced.

However, Jesus warned us that such confusion comes from “the Devil… a liar, and the father of [lies]” (John 8:44), and his Apostles explained that “God is not the author of confusion” (I Corinthians 14:33), but rather God gives “understanding, that we may know [what] is true” (I John 5:20).

Thus, the labyrinth of secret complexities associated with “Common Law” strategies is actually a deception as a distraction, to mislead rights advocates away from the simple truth of fundamental rights in real Common Law.

True Common Law is really the formal recognition of timeless universal rights and obligations, under God’s Law as Natural Law, which is essentially basic concepts of fairness, which are traditionally known plainly as common sense.

The Templar Prince Grand Master of the modern Templar Restoration, the Barrister Matthew Bennett, summarized this by coining the maxim: “Common Law is really common sense.” (ca. 2018)

Therefore, any confusing complexities of secret practices, requiring academic acrobatics to simply assert fundamental rights, are “not of God”, and do not belong to the legitimate effective practice of Common Law jurisprudence.

The true Common Law of the Templar Magna Carta tradition is firmly grounded in fundamental principles of right and wrong, fairness and Justice, and driven by underlying and overriding protections against abuse of power. Thus, any secret complexities or subtle technicalities which could artificially tip the scales of Justice are categorically excluded from Common Law jurisprudence.

This is “the power of fundamental principles”, that in all simplicity of natural Truth, they have the penetrating ability to cut through all confusion and distractions, to reveal a universal balance, which satisfies the basic human conception of the common-sense understanding of Justice.

A famous metaphor for this comes from Victorian historians of ancient rules of nobiliary and chivalric institutions, describing complexities of the courtly practice of tying “cravat” neck-scarves, in particular the infamously difficult “Gordion knot”:

“Alexander the Great, irritated at being unable to comprehend the theory of its composition, and determined not to be foiled, adopted the shortest and easier method of solving the question [problem] – that of cutting it with his sword.” ((H. Le Blanc, Esq., The Art of Tying the Cravat: A Pocket Manual, Effingham Wilson, Cornhill, Ingrey & Madeley, The Strand, London (1828), “Lesson II: Noeud Gordien”, pp.30-31.))

This historical anecdote is the origin of the colloquial expression “cutting the Gordion knot”, meaning to cut through distractions, to simplify an overcomplicated situation, and achieve a direct common-sense result.

This is the authentic nature of the real Common Law of the Templar Magna Carta, that fundamental principles, of clear and balanced doctrines of law, directly and swiftly “cut the Gordion knot” to deliver effective Justice.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The heritage of this primary Templar mission mandates that all projects of the Templar Order must maintain a dedicated focus on defending and advancing the Rule of Law and People’s Rights in modern international law. This requires all Templars to uphold fundamental rights and freedoms against arbitrary abuses of power by modern governments and corrupt officials.

It is highly significant that in the 13th century, the Templar Magna Carta campaign to establish the first People’s Rights and principles of constitutional law arose by necessity, in response to increasing abuses of authority by the monarchy.

During those times, abuses against rights were driven by the need to pay for failed foreign wars, as a result of pursuing a policy of aggressive imperialism. This led to confiscation of property and denial of rights, in violation of existing laws.

The solution given to the world by the Knights Templar, which improved essential freedoms and the welfare of humanity for many following centuries, was the Magna Carta and its resulting Civil Rights and Human Rights under a meaningful Rule of Law.

Modern times (from the 20th century) have also witnessed relentless and escalating military aggression (overt, covert, and by proxy), promoted by Globalist political factions manipulating dominant countries, in flagrant violation of international law.

As a direct result, the modern governments which claim to represent ‘democracy’ have also been severely weakened by their own failed foreign wars, as a consequence of pursuing Globalist policies of neo-imperialism and neo-colonialism, as a Socialist form of neo-feudalism.

As a further consequence, this has also led to escalating abuses of authority, deprivation of rights and property without due process of law, and generally rampant violations of rights.

Therefore, humanity now faces precisely the same problem in the modern era, and for the same reasons, as the Knights Templar faced under medieval monarchs.

In modern times, exactly the same problem requires to reassert the same effective solution. The original and restored Templar Order is now needed once again, to defend, restore, promote and enforce all international law, to reclaim People’s Rights and the Rule of Law itself for all of humanity.

Depiction of inscription on the bell of JFK’s Honey Fitz yacht, reportedly added to the bell ca. June 1963, symbolically portrayed in the movie “White Squall” in 1996

The Temple Rule gives all Templars a mandate to overcome “the isolation of their own wills” (Rule 1), through “Holy service” manifesting their collective will (Rule 39), “[not] according to one’s own will, but according to the commands” of the principles of Chivalry (Rule 41), as the Templar “way of life” (Rule 274).

This is a core principle that while the Templar Order is essentially one of independent “leaders, not followers”, all Templars are individuals united in Chivalry, combining the strength of their separate wills, channeling their individual wills into a common cause, for collective impact for The People against anti-humanitarian agendas.

Accordingly, while only some members of the Order may have the specialized legal skills needed for Magna Carta related missions, all Templars contribute indirectly through supporting efforts, and thus all share in the collective accomplishments of restoring and upholding the Rule of Law.

This principle of collective Chivalry is best expressed by the bell on the Honey Fitz yacht of the American President John F. Kennedy (“JFK”), who most famously declared the fight against governmental corruption worldwide, which reportedly displayed the inscription (added ca. June 1963): “Where We Go One We Go All”. (The coded acronym for this expression is ‘WWG1WGA’.)

This saying is believed to come from JFK’s Navy service during World War II as Commander of the Patrol Torpedo boat “PT-109” in 1943. (The bell and inscription was portrayed in the 1996 fiction movie “White Squall”, symbolically depicting the spirit of the Kennedy administration, which JFK called “Camelot” named after the Arthurian knightly legends.)

You cannot copy content of this page

Javascript not detected. Javascript required for this site to function. Please enable it in your browser settings and refresh this page.